Where History Meets Art: The Work of Jewish artist David Labkovski

The LAUSD is piloting a program here in the Valley—The David Labkovski Project—aimed at teaching students about the Holocaust.

-

CategoryPeople

A life, A memory

Before the wave of genocide, that latches on and never lets go

Before the reign of terror, the separations – the hope that was lost

That stole so many lives that scarred them too. How you want, how you wish to forgive, to forget.

But never will.

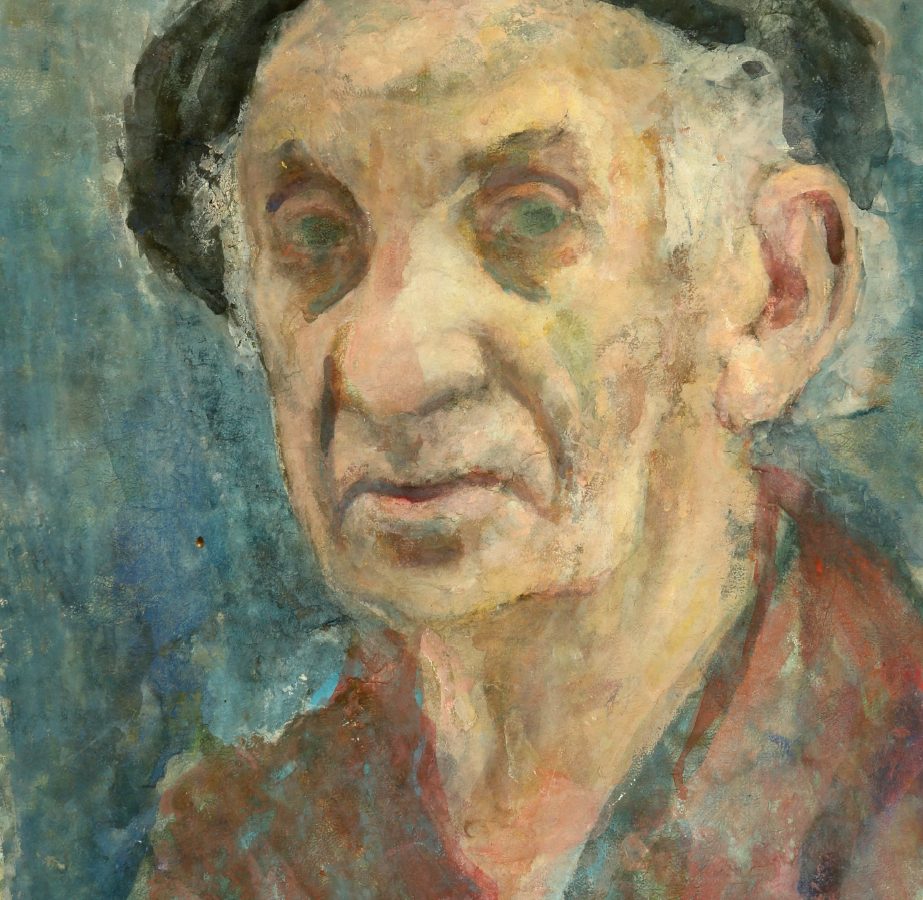

The life of Jewish artist David Labkovski was filled with tragedy. Born in Lithuania in 1906, he survived three years of imprisonment in a brutal Siberian gulag during World War II. He then returned to a devastated Lithuania, where over 95% of the Jewish population perished in the Holocaust. Throughout Labkovski’s life (He died in Israel at the age of 85.), he painted the story of his struggles and those of his community—the vanished, as well as the people and places that survived. “If it was a choice between a cup of coffee and paints, it was always paints and paintbrushes,” his great-niece Leora Raikin says of David and his wife, Rivka. “Their entire life’s focus was securing paint supplies in whatever form, to be able to document what had happened.”

Today, thousands of miles away in California, the artist’s work is the foundation of the nonprofit David Labkovski Project. The organization is using the artist’s powerful paintings to teach school kids about the Holocaust—and more. Founded by Leora, an artist and educator, and longtime educator Stephanie Wolfson, the DLP has piloted an innovative educational program in four schools, including two in the Valley: the Abraham Heschel Day School in Northridge and Daniel Pearl Magnet High School in Lake Balboa.

Over the course of a semester, Leora and Stephanie go into classrooms once a week, with copies of Labkovski’s paintings. Students learn about his life and are encouraged to critique and respond to his work with their own artwork and poetry. The semester culminates in a student-led exhibition of Labkovski’s art. “The ultimate goal is for them to be able to curate an exhibition that they have designed,” Stephanie explains. “They have selected the pieces for it, and they have collaborated with each other on how to tell his story in a historical context.”

“Traditionally a lot of Holocaust history has been taught either through survivor testimony or reading a document,” Leora says. This project, she explains, is “much more than just Holocaust education—it’s the creation experience, it’s the ownership, it’s the critical thinking skills, it’s the public speaking, it’s reading art.”

Students are given enormous freedom in how they choose to display Labkovski’s work. “When we say it’s up to them, it really is up to them,” Stephanie says. “So we have our lesson plans to explore the history and the art, and then we’re like ‘What are you going to do with this?’ The question we ask is, ‘So now, how do you want to tell the story? How do you want to curate it for the public if you are not there to docent?’”

The kids have responded in innovative ways. At Heschel Day School, students decided to use QR codes (matrix bar codes) in their exhibition, so that visitors could listen to information about each piece of art on their smartphones. Another school chose to create a website to serve as a companion piece to its exhibit, ensuring the project lived on after it closed.

Leora and Stephanie hope to expand the program nationwide and continue Labkovski’s lifelong mission of bearing witness. The two enthusiastically share student comments. One student told Stephanie, “If anyone ever tries to deny this [the Holocaust] happened, they need to come to me!” Another student, while drawing a portrait of Labkovski, said, “I thought I understood how hard his life was, but when I was drawing the lines on his face, I felt it.” Perhaps empathy is the project’s greatest lesson.

Architect May Sung Comes to The Rescue on a Studio City Reno Gone Wild

In the right hands…finally!