The First Flip

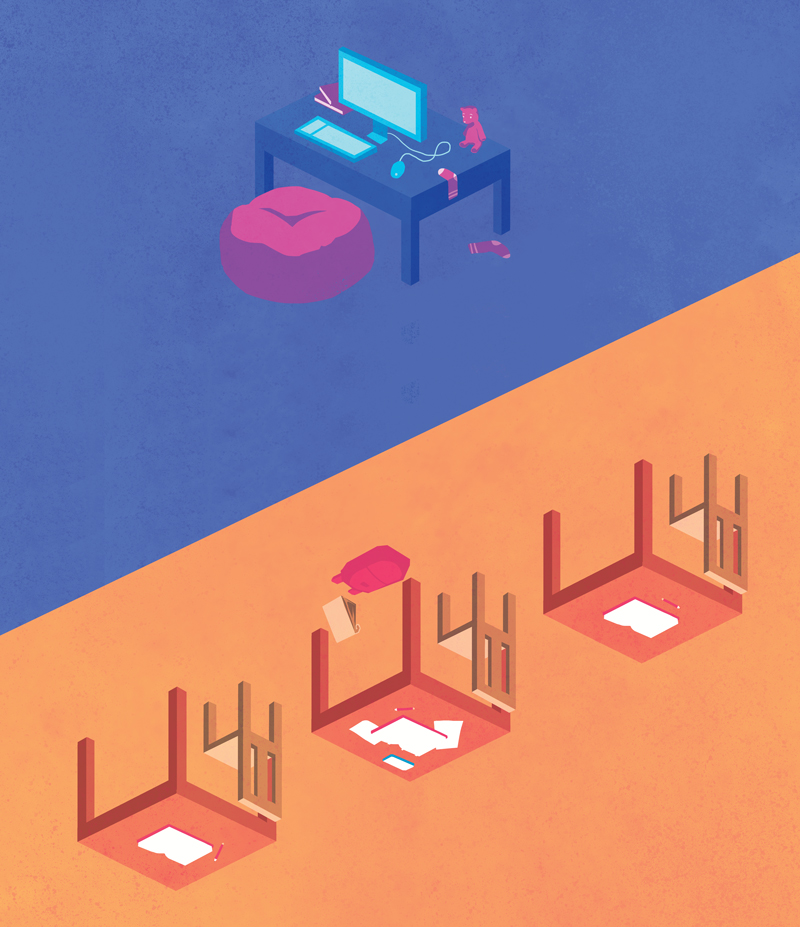

An innovative teaching technique called The Flipped Classroom is inspiring local educators to reach students in new and sometimes more effective ways.

-

CategoryPeople

ILLUSTRATED BY CHRISTINE GEORGIADES

ILLUSTRATED BY CHRISTINE GEORGIADES

The flipped classroom first gained national notice in 2007 when Colorado high school teachers Jonathan Bergmann and Aaron Sams started videotaping their chemistry class lectures and posting them online for absent students. In 2012 the pair launched the Flipped Learning Network (flippedlearning.org), a nonprofit that offers tools and an online community to educators using or interested in flipping.

A sign on the wall of Joanne Ryan’s classroom at The Buckley School in Sherman Oaks warns: “There’s no crying in calculus.” Tears may be prohibited, but chattering among students is not only allowed, it’s encouraged. Throughout Ryan’s 75-minute AP calculus class, students actively converse with one another as they work in pairs to figure out the length of an arch. Meanwhile Ryan, who chairs Buckley’s math department, walks up and down the rows of desks offering help.

As for the lecture where Ryan explains exactly how one goes about calculating the length of an arch? The group of 24 students, which includes sophomores, juniors and seniors, had watched it beforehand at home on their laptops.

Welcome to “the flipped classroom,” a relatively new and innovative teaching method that’s caught fire in recent years. Educators are using it now in middle and high schools, as well as colleges, universities and even medical schools across the country, including here in the San Fernando Valley.

ABC’s of Flipping

The premise is quite simple and in some ways a reverse of the way most of us were taught. Students are introduced to new material in bite-size video clips at home. During class time, the instructor and peers are available to lend support for solving problems that would traditionally be given as homework. Class time is also used for discussing concepts in depth and group projects.

Flipping, also called inverting, is especially popular in math and science classes, subjects in which homework can often be frustrating, but it’s also being used to teach foreign language, history, English and other courses.

Proponents say the benefits are multipronged. “A lot of students don’t take good notes in class, then they go home and have to do 40 problems and don’t know how,” explains Andre Wiseman, who’s been flipping his geometry class at Campbell Hall School in Studio City for the past five years. A former movie producer for whom making videos came naturally, Wiseman honed his flipped approach teaching algebra and geometry at the Oakwood School, also in Studio City.

With the flipped model, “The majority of the work is done in class where I’m there and students’ peers are there to help,” the geometry teacher adds. “Sometimes their peers explain things in a better way that makes the light bulb go off.”

Not only that, “Working with partners keeps me more focused in class,” says Caroline Bloch, a junior in Ryan’s AP calculus course.

Another major advantage, says Ryan, “At home students can learn the material at their own pace. They can go back and rewind. Kids don’t all learn at the same rate. In a class lecture you may not get something, but before you can ask a question the teacher has already moved on to three new concepts.”

An energetic woman with a fast-paced teaching style, Ryan discovered the flipped concept at a number of conferences and introduced it at Buckley with a single AP calculus class in 2014. It was such a hit that the approach is now used at the school to teach AP statistics, regular calculus, geometry, algebra and life science.

The Mechanics in Motion

Flipping is being embraced by teachers at schools with diverse populations, ranging from Westmark School in Encino for students with learning differences to Ingenium Charter Middle School in Winnetka, which serves low-income, minority students. It’s also used at several independent college-prep schools.

For Westmark students, home video lectures offer an effective multi-modal opportunity to help those with memory issues better retain information because the material can be paired with music, visual imagery and humor, according to upper school history teacher Jeffrey Jiminez.

Take for example a recent video lesson Jiminez posted on “Substitutes and Complementary Goods,” for students in his economics class. In it Jiminez visits a MAC cosmetic store in the mall and a Target store, comparing the price of comparable lipsticks.

“The power in teaching is when you have time to mentor and coach. I now have more time to do that. I feel like i now get to know the students and their strengths and weaknesses better.”

Flipping is just “another tool in the tool box,” he explains. “We seek to make the curriculum accessible. Forcing a student to read something they won’t remember when they’re done isn’t helpful.”

At the Ingenium Charter Middle School, flipping is also viewed as one of many innovative tools used to make learning more engaging and effective, according to David P. Langford, president/superintendent of Ingenium, which operates four charter schools in Southern California.

The 3-year-old charter is about to embark on its own version of the pedagogy. Students who are ready to move on and explore a new concept, whether in an art class or English class, arrange a workshop with their teacher. Anyone can join the workshop, but even those who don’t can get the lesson later, when they’re ready. One student is assigned to video the instruction, which the teacher then posts online. That way students can access it at a later time, including those who want reinforcement.

“It provides options as to how a student wants to go about learning,” explains Langford. “Some need a lot more repetition, which in real time can be frustrating to other students.”

Keys To Success

Valley teachers concur that the key to an effective video lecture is keeping it short, between seven and 15 minutes per concept. Most teachers also say they continue to tweak their videos year to year. Ryan, for example, added a couple of practice problems at the end of each video lecture when a student suggested it would be helpful to have some immediate practice utilizing what she’d just learned. Some, such as Jiminez, also use third party-produced videos to supplement their original fare. Students as a whole, they add, love the new approach.

“In the beginning I personally didn’t like it because I usually ask questions in class,” says Buckley senior Brittany Nazar. “After I got the hang of it though, I thought it was more useful because studying for tests, I could rewatch and relearn the lesson or ask a question during the teachers’ office hours.”

Some parents are initially skeptical too. “Some have said, ‘Why am I paying all this money if my child is watching a video?’” admits Campbell Hall’s Wiseman. “But I say, ‘It’s a video made by me. It’s exactly what I would have been doing in class.’ Also, when the students come in after watching the video, I may go through the slides of the video with them. I offer guided note-taking and offer fill-in-the-blank notes and exercises.”

What matters most of course, is how teachers use class time. “There’s so much more to being a high-quality teacher than being a good lecturer,” says Ramit Varma, cofounder of Revolution Prep, a leading tutoring firm that also produces instructional videos used in a number of public charter schools throughout the city. “These tools are designed to take away that lower-value work that teachers do.”

Kelley Skahan who flips her Algebra 1 class at Viewpoint School in Calabasas agrees. “The power in teaching is when you have time to mentor and coach. I now have more time to do that. I feel like I now get to know the students and their strengths and weaknesses better.”

As for whether the flipped classroom improves test scores, most detailed research has been conducted at the college level. Despite results of a four-year research pilot at Harvey Mudd College in Claremont that reported no difference, the majority of research suggests that it does help. Studies at San Jose State University, the University of Washington and Villanova in Pennsylvania all report remarkable improvement.

Ryan hasn’t measured test scores, but says without hesitation, “There’s definitely been improvement in the area of enjoyment, a feel for the material and class time passing faster.”

Architect May Sung Comes to The Rescue on a Studio City Reno Gone Wild

In the right hands…finally!