My Time with Johnnie

Most of us remember Johnnie Cochran as the “if the glove doesn’t fit,

you must acquit” attorney who cleared O.J. Simpson of murder charges. But for one young law clerk during the early ‘70s, the swashbuckling lawyer was about much more than one notorious verdict.

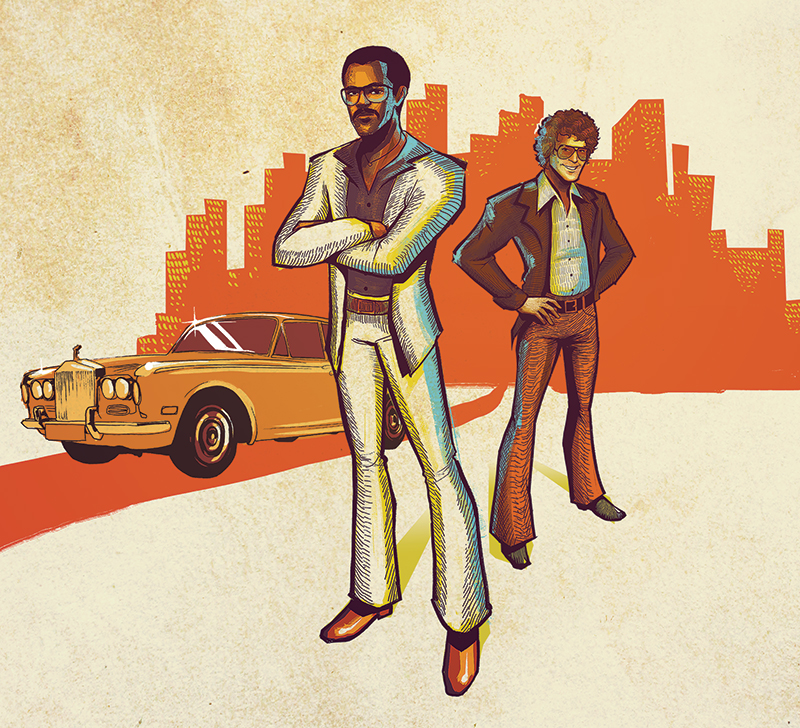

Written by Arnold Barry Gold | Illustrated by christine georgdiades

-

CategoryPeople

-

Written byArnold Barry Gold

As the Mad Men era gave way to disco, there was a brief, nameless period of time between the love beads and the gold chains, between Charlie Manson and Patty Hearst, between Hair and Boogie Nights and, more specifically, between my National Guard service on the mean streets of Watts and Watergate. The rewind button of my memory pauses on an unlikely journey down a veritable “yellow brick road,” which still goes by the name Miracle Mile.

In 1970 LA was very much a place where total self-invention was still possible and where the drive from my “night” law school in the flat obscurity of Northridge to a high-rise law office on Wilshire Boulevard did not encompass nearly as much traffic time as today—but constituted a vastly greater distance for the imagination.

After class one evening, my torts professor, attorney Steven Fleishman, asked me if I would be interested in a law clerk position. I responded affirmatively, figuring this would better prepare me to practice law than working in my dad’s dry cleaning plant on Santa Barbara Avenue.

Fleishman asked if it mattered to me if the lawyer was black. I (with my “afro”) responded, “Not in the slightest.”

“Good, the lawyer’s name is Johnnie Cochran. His office is on the Miracle Mile, Wilshire and Western, across from the Wiltern Theatre.”

To a kid who was raised in the drab, gray cold of Chicago, Wilshire Boulevard was far more than an ordinary street. Both literally and figuratively, it was the direct pathway to the “Hills of Beverly.”

Moreover, my wife, Bobbie, was excited by the address, saying that Downtown LA was about as exciting as Akron (which she knew quite well after being raised in a small Ohio town). Wilshire Boulevard had cache, she insisted, with the new LACMA, the spectacular Ahmanson Plaza, the gold-and-black art deco May Company and many other beautiful buildings.

Wilshire Boulevard also took you west into the setting sun, into the blinding LA light, right to the edge of the continent. And, for me, that meant entirely new territory.

And so a few days later, dressed in a blue blazer, grey slacks, powder blue shirt, wide multi-colored tie with an even wider knot, I grabbed the door handle of the double doors inscribed with the names Cochran, Atkins & Evans in block gold metal letters. I can remember the large waiting room of the law office on the eighth floor of 3810 Wilshire Boulevard like it was yesterday.

There were dimly lit lamps on glass and chrome tables; avocado-green, deep-shag carpet; a black leather sofa; two matching Wassily chairs; and a prominent photograph of Justice Thurgood Marshall. This was accompanied by numerous other photos of an always-smiling Johnnie L. Cochran, Jr. with assorted judges in black robes and other notables of the day. Authentic African art sculpture accented the room, but what caught my eye was a notebook entitled “Deadwyler” on one of the glass tables.

The notebook outlined a case involving Leonard Deadwyler, a black man who was shot dead by police as he tried to rush his pregnant wife to the hospital in 1966.

The notebook outlined a case involving Leonard Deadwyler, a black man who was shot dead by police as he tried to rush his pregnant wife to the hospital in 1966.

Johnnie represented Deadwyler’s family. He accused the LAPD (who claimed they acted in self-defense) of brutality. The DA’s office did not file charges.

I was impressed. Vietnam was still raging, and racial discrimination was prevalent. Like so many students, I was a liberal and a bit militant, given to wearing a button featuring the Black Power fist.

After proving at the coroner’s inquest (to much fanfare) that Deadwyler “died at the hands of another,” the firm lost the civil suit. But one reporter after another raved about Johnnie’s suave demeanor, style and intelligence. Clearly he was an “attention-getter,” and I liked that.

When I first met Johnnie, he was seated behind a huge desk with floor-to-ceiling windows facing west, the sunshine pouring in. He wore a neatly cropped afro, blue aviator sunglasses, green velour suit and an extremely wide blue tie. Files were piled high on his desk.

As I entered the room, Johnnie’s two law partners, seated in matching “client” chairs, stared at me. Nelson Atkins was long-legged, thin, distinguished-looking, wearing a dark three-piece suit. Irwin Evans was football-player large, light-skinned, with distinctive reddish hair. Both Johnnie and Nelson warmly rose to shake hands, but Irwin remained seated.

“Call me Johnnie. Steve Fleishman speaks highly of you … says you’re intelligent, not afraid to speak up in class.”

“Who am I to disagree with my torts teacher? Glad to hear he likes me,” I said.

Irwin apparently felt the need to say, “He didn’t say he liked you…” to which Johnnie replied, “Man, that is vicious”—an adjective Johnnie habitually used.

Johnnie asked if I was currently working. I responded that I worked at my dad’s dry cleaners on Santa Barbara Avenue just west of Crenshaw, which elicited another sardonic comment from Irwin. “Exploiting black folks there in the ‘hood, do you?”

“Not hardly, Mr. Evans,” I replied. “My family’s been in the dry cleaning business for decades, both in Chicago where I was born and raised and here in LA. We provide a quality service and know how to treat our customers.”

Nelson asked if I’d ever clerked before, to which I said, “No sir, but I learn quickly.” Johnnie then said, “We need a full-time law clerk. Do you know your way around a law library?”

“Yes, sir,” I lied (gulp).

“Have you learned to draft pleadings, interrogatories, complaints, stuff like that?”

“Yes sir”—another semi-lie. “And what I don’t know, I’ll learn.”

Irwin then asked how I would feel about working for a black law firm. Not missing a beat and with an arched eyebrow, I inquired, “Are you gentlemen black?”

“OK, kid,” Johnnie chuckled. (He frequently call me “kid” even though I was only seven years younger than he was.) “We’ll give you a try. Be here at 10 a.m. tomorrow.”

The next morning, I drove my new white 1969 XKE Roadster, wire wheels, red leather interior, top down to the Law Offices of Cochran, Atkins & Evans—Day 1 of what would become a 43-year legal career. Johnnie, in his white Eldorado (one of many “caddies” and Rolls-Royces he would own—all always white) immediately followed me into the parking garage.

“The perfect car to serve subpoenas in Compton,” he said, appearing to enjoy the irony of “the kid” driving to sketchy parts of town in the white XKE.

I was led to a smallish room/law library with a conference table and chairs at the rear of the office, which became my particular base of operations for the next three years. I was told to start putting the law books back on the shelves and to join Johnnie, Nelson and Irwin for their lawyers’ meeting at noon.

Sometime after noon, Nelson directed me to Johnnie’s office for the “calendar meeting,” with instructions to “take notes, don’t talk.” Johnnie was behind his desk, Irwin was seated in a client chair, and their attorney day books were open and in front of them.

It became immediately clear that in a busy law practice, it was absolutely essential to lock down and coordinate which attorney will be covering what court appearance and what the desired objective is at that particular appearance. Over the next three years, I learned that precious little is more important than being efficient and well-prepared for every court appearance.

Johnnie mentioned matter-of-factly that there were nine cases on the firm’s calendar the next morning, to be divided among the three of them. And all nine cases were called for at 9 a.m. in far-flung places like Santa Monica and Torrance! (Three guys in nine places, many miles apart, all at 9 a.m. … hmmm.)

I remember wondering how they would pull this off. But they did, beautifully and expertly. “I’ll take this case, you take that case…” and so on—multiple arraignments, preliminary hearings, trials, depositions, you name it.

They handled it and in the courtrooms of some of the most colorful jurists in LA County history: Armand Arabian, who would take the bench with a loaded pistol under his robe (and who would become a California Supreme Court Justice and a personal friend); William “Bill” Keane, for whom a stretch of the Harbor Freeway is named; and Noel Cannon, the miniskirt-wearing, derringer-packing judge who would take the bench with her Chihuahua in her lap and who would later be removed from the judiciary for numerous improprieties—among them, displaying a sign in her chambers that read “Vasectomies Available, Inquire Within” with a diagram of her derringer beside it.

Lesson #1 I learned from Johnnie: Always be kind and courteous to the employees of the court. Over those early years, it would never cease to amaze me how positively charming and polite he was to everybody (especially the ladies)—from the janitors in the halls to the judges on the bench.

Indeed, every time I was in court with him, every lawyer present in the courtroom would come up, shake his hand, share a story or two, smile, laugh and vice versa.

In later years, his courtroom style and demeanor would become legendary as it was broadcast live across the world during the infamous O.J. Simpson trial.

We were always laughing, especially at lunch. I’ll never forget the first time I was invited. Johnnie said, “Let’s introduce the kid to some soul food. We’ll take him down to Murray’s there on Santa Rosalia. Tell the girls we’ll leave in 15 minutes. I’ll drive,”

A table for six (became the familiar future refrain): Johnnie, Nelson, Irwin, secretaries Albertine and Cecilia, and me. On this particular day, I’m sure mine was the only white face in the place. On Johnnie’s recommendation, I ordered the smothered pork chops with yams. Chit-chat ensued; I listened and observed.

Johnnie was taking me to a preliminary hearing before the pistol-packing Judge Noel Cannon to “expose” me (gesturing the “quotes” signs with his fingers) to some of the finer aspects of our judiciary. Nelson and Irwin both chuckled (first time I noticed Irwin had teeth.)

BAM!! The front door flies open. A guy runs into the restaurant, followed immediately by two LAPD officers with guns drawn. Simultaneously Johnnie, Nelson, Irwin and the girls dive under our table, out of the line of fire. I’m stunned, not moving. Johnnie yanked me under the table. Then, peering out, I see the cops apprehend the guy, cuff him and lead him out of the restaurant.

BAM!! The front door flies open. A guy runs into the restaurant, followed immediately by two LAPD officers with guns drawn. Simultaneously Johnnie, Nelson, Irwin and the girls dive under our table, out of the line of fire. I’m stunned, not moving. Johnnie yanked me under the table. Then, peering out, I see the cops apprehend the guy, cuff him and lead him out of the restaurant.

You have to remember, LA was a smaller town then—a city reflecting my own angst in a state of head-jerking flux. My perspective, as a 26-year-old, fresh from the chaos of the last five years (’65 to ‘70), left me ready to absorb just about anything and everything.

I had served with the National Guard on the streets of Watts. I’d marched at the Century City protest rally. One of my best friends was the national secretary of the powerful, left-leaning activist group Students for a Democratic Society. All the while, I curiously reflected on my father-in-law’s extreme Barry Goldwater conservatism.

Irwin’s remark that this “stuff” happens all the time in the ‘hood left me slightly horrified. It was the first time I ever saw police with guns drawn, and I remember thinking: This is not a movie.

Irwin added, only half kidding, “Yeah, good practice for when we have you serve subpoenas. By the way, you do own a bulletproof vest?” I realized that this was not going to be your average clerkship.

Over the next three years I traveled far along the Miracle Mile at varying speeds, meeting and working with—and against—some of the “greats” like Marvin Mitchelson, Gloria Allred, Howard Weitzman and Bob Shapiro, to name just a few. But Johnnie was truly the first rock-star lawyer. In some cases the media covered him as much as his famous clients.

In reflecting on the notoriety and scandal of the O.J. case that followed many years after I left the offices of Cochran, Atkins & Evans, I see how Johnnie was perfectly cast to play his indelible role in that high legal drama. Indeed, it was reality TV at its very best.

My license admitting me to practice before the Supreme Court of the United States of America hangs above my desk. It reflects that I was admitted on the motion of Johnnie L. Cochran, Jr., in 1977. It remains one of my most prized possessions.

I am now several years older than Johnnie was when he died. I see that he was part of an LA that, for the most part, no longer exists. The Miracle Mile is still there, though I now rarely drive it—perhaps because I can no longer see it as leading to the possibility of self- invention, which certainly still exists here but which all seems far more calculated now, more produced, more strategized, less joyful. Few people nowadays seem to compare to the entourage of larger-than-life characters I met during those years, especially Johnnie.

Sometimes in the late afternoon, when the sun pours in through the windows and hits the glass just right, I can see a green shag-carpeted law office that looks like it could be a stage set for a cable TV show with a theme song from Motown. My mind wanders back along the Miracle Mile, through the haze of years, and I remember my time with Johnnie.

Encino resident, Arnold Barry Gold, recently retired practicing law at his business and complex civil litigation firm. “My Time with Johnnie” is an excerpt from a TV pilot he’s currently pitching entitled Miracle Mile.

Architect May Sung Comes to The Rescue on a Studio City Reno Gone Wild

In the right hands…finally!