Home of the Brave

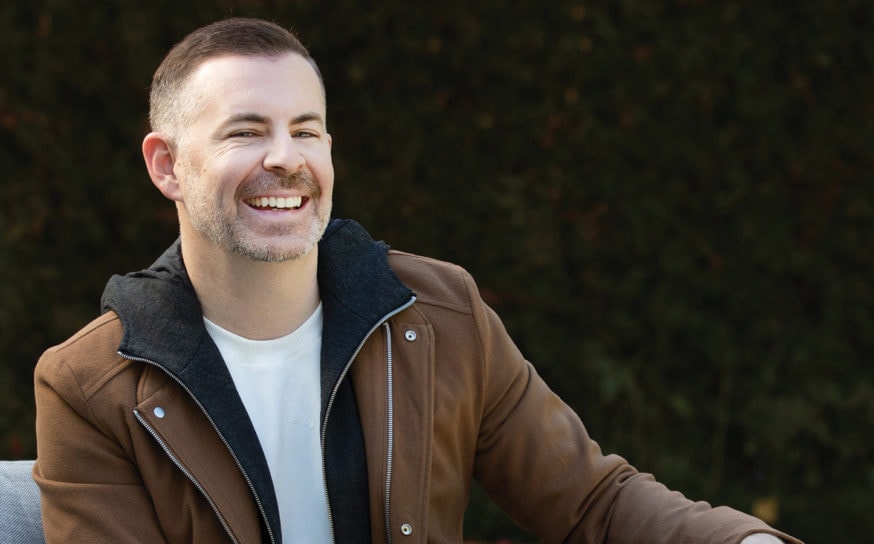

For most people, the name Daniel Pearl brings to mind a journalist who died at the hands of al-Qaeda. But here in the Valley, where Pearl grew up and his family still lives, locals remember “Danny” very much in life. And now, on the heels of the 10-year anniversary of his passing, they are celebrating his legacy.

-

CategoryUncategorized

-

Written byLara Vancans

The first time lifelong friend Cammie McGovern met Daniel Pearl, he was a seventh-grader at Portola Junior High in Encino, dressed as his favorite literary character for an oral book report project. He was decked out as the intrepid Huckleberry Finn—complete with homemade fishing pole—leaving an indelible mark in her memory.

“‘We were all 13 years old at the time, new to junior high and acutely self-conscious. ‘You don’t have to wear the outfit all day,’ we pointed out. ‘What?’ he grinned. ‘Why not? I look so good.’”

Huckleberry Finn, the insatiable adventurer from Mark Twain’s controversial, 19th-century novel, made the world think about the possible dangers of entrenched misunderstanding. Sound familiar? The foreshadowing is beautiful in its blatancy.

The world knows Daniel Pearl as the journalist whose impassioned pursuit of truth came to a devastating end at the hands of Islamic extremists in Pakistan a little more than 10 years ago. He was living in Bombay with his pregnant wife, Marianne, and was in Karachi tracking connections to “Shoe Bomber” Richard Reid.

As written in The New York Times in 2002, his death couldn’t have been more ironic. While seeking to generate informed accounts of Islamic fundamentalists post-9/11, the very people whose story he sought to voice were the people who silenced him.

The man the world was tragically introduced to in 2002 became a symbol of peace, knowledge, freedom and individuality. He has become iconic. And this past March, with another recent arrest associated with his murder, Daniel Pearl is still making headlines.

But for those who grew up with him here, his memory lives on in a different, personal, poignant way. They knew the caring, inquisitive, bespectacled guy as just “Danny.”

It’s his humor, warmth, love for music and his effortless intelligence that they remember—the man who read the border-defying language of music before words, who debated the nuance of Springsteen lyrics with a vengeance, and who hung out at Robb’s Ice Cream Parlor in the Valley. They remember the Danny Pearl who didn’t always have everything figured out.

“It wasn’t obvious what he would do. But I knew he would do something great,” says Danny’s childhood friend, Robbie Gershowitz (née Glick), a USC grad, mom and tax accountant who still calls the Valley home.

Cammie, who is now a fiction writer based in Massachusetts, remembers the first time she and Danny, as new college graduates, discussed “what years of compulsive letter writing had made clear.” Together, in her Astoria, Queens apartment, as Danny passed through on his way to a skiing trip, they dreamed of being writers. “Maybe fiction; maybe journalism,” he said.

While Danny’s family lived in Israel during his eighth grade year, he and Cammie exchanged letters. “Not because we were ‘dating’ in that junior-high, confusing, meaningless way, but because, I suspect, even back then we were both people who secretly pined to be writers. We liked distilling our experiences into anecdotes and liked coming home and finding letters in our mailbox. We also both worked hard on being hilarious,” Cammie shares.

THE EARLY YEARS

Danny was raised on Ballina Canyon Road in the hills of Encino with his mother and father, Ruth and Judea, and his two sisters, Michele and Tamara. (The family did not respond to requests for interviews). He attended local public schools: Lanai Road Elementary, Portola Junior High and Birmingham High School.

Robbie, who attended all three schools with Danny, remembers the Pearls fondly. “They were a lovely, warm family, and Danny treated his friends, even his acquaintances, with warmth. He was a mensch.”

She also remembers the whole family’s love for music, as inspired by Judea Pearl’s acclaimed career as a choral conductor. Like his father, Danny was an avid musician. He learned to play piano by age 4, and by high school the violin had captured his heart. “Nothing stunned me more than the surprise of how good he became in such a short period of time,” says Cammie.

Pearl in the 1981 Buckingham High School yearbook

“His favorite instrument was the violin, because he could carry it around,” recalls Narda Zacchino, executive director of the Daniel Pearl Foundation. Like his work, it moved with him. “He used music to gather people together; it didn’t matter what their beliefs were … or their politics.”

In high school, Danny was part of the popular crowd, recounts Robbie. “But Birmingham was different then. The popular clique wasn’t necessarily all the athletes. It was the really smart, overachieving kids. One day a week, Danny and his circle of friends would eat lunch with their French teacher as part of an immersion program. It didn’t define him, but it was something he would do.”

Cammie, too, remembers Danny’s natural affinity for French, a subject that was not her forte. “By high school, we were part of a high-achieving crowd which Danny floated to the top of pretty effortlessly. This was excruciatingly true in French, where I labored over verb conjugation flashcards and sweated out my meager four-word replies to Madame Leisner, while Danny doodled on his sneakers and held up his end of 10-minute conversations in French.”

Though he demonstrated an early affinity for writing, Danny didn’t write for his high school newspaper—there was no student newspaper at Birmingham when Danny was there. When he arrived at Stanford in 1981 to pursue a degree in communications, Danny created his own writing and reporting opportunities, cofounding a student newspaper, the Stanford Commentator, and reporting for the campus radio station, KZSU.

But most of all, Danny’s friends remember his laid-back ease. He was smart—perhaps the smartest in the class, but he cared about other things like his music, being funny and his friends.

“He was very quick to smile; he had a wit,” Robbie explains. “He wasn’t the one to go out there and be the cheerleader, but he wasn’t going to create drama or pick a fight. He was just a good guy. We were all idealistic, and he stayed that way.”

Pearl with his fifth grade class at Lanai Road Elementary in 1973 (second row from top, third from right).

COMMEMORATING DANNY

Today Danny’s memory is kept alive not just by friends and family, but by an institution. The Daniel Pearl Foundation was established just days after Danny’s death to promote the principles he stood for: tolerance, the efficacy of education and communication, and a love of music, humor and friendship.

While she never met Danny, Narda Zacchino has dedicated her working life to diminishing the hatred that led to his demise. “He was a citizen of the world. He liked to bring people together, and he used his writing that way,” she says.

As executive director, Narda is particularly proud of the foundation’s visiting fellows program. Each year since Danny’s death, the foundation has sponsored two mid-career foreign journalists from the Middle East or South Asia to work in major U.S. newsrooms, such as The New York Times and Los Angeles Times.

Notably, each visiting journalist also spends time at The Jewish Journal of Greater Los Angeles. “For many, this is their first time meeting a Jewish person,” shares Narda.

In October 2002, for what would have been Danny’s 39th birthday, his family decided to celebrate the way he would have—with friends and music. From this idea sprang another commemorative project: the World Music Days program, “an international network of concerts that use the power of music to reaffirm our commitment to tolerance and humanity.” Now, the month of October plays annual host to more than 10,000 performances in more than 129 countries. Even Elton John has participated in the event.

And here in the Valley, adjacent to Danny’s high school alma mater stands the Daniel Pearl Magnet High School, which was named in 2007. David Jay, former magnet school coordinator, led the naming project after attending an advance screening of the documentary The Journalist and the Jihadi.

As a Los Angeles Unified School District magnet school for journalism and communications, “it seemed right that our magnet should be identified with a significant role model in journalism,” David offers, adding that Danny “attended Birmingham High School, where the magnet was anchored at that time.”

For the magnet school faculty, Danny’s memory is a moral compass. “Danny Pearl is a part of the culture of this school,” explains principal Deb Smith. “The students are all oriented to his story. We use what he stood for as a reminder, a measure of what we expect out of our students to give back to the community, to give back in service. If we are dealing with a conflict, we’ll often imbed it into the conversation: ‘What would he say right now if he were in this room?’ The kids really kind of get put in check when we bring that in.”

The principal didn’t know Danny either, but like Narda, she feels she knows his “essence.” She says, “The kids at this school step up, and that’s because it’s conveyed through Danny, his legacy: This is what is expected; we take care of each other.”

And Danny did care. He was the peacemaker, according to Cammie. She described a morning at Birmingham High School when insults among friends, half in jest, were flying. Danny lay down on the ground in front of the wall where their group of friends met every day before classes and pleaded, “Why can’t we all just get along?” Everyone then proceeded to pile their backpacks on top of him, and he was literally “a muffled voice of reason, a leader from behind,” she remembers.

Danny’s search for peace in the world continues to this day. What is more measurable is the number of people, like Narda, Cammie, Robbie, Deb and many others, who are inspired by his unfinished mandate.

Just after the first time they spoke of their dreams to write professionally, Danny left a book with Cammie: At Home at the End of the World by Michael Cunningham. Years later, after Danny’s death, Cammie found a quote from the book scribbled in his “crabbed” handwriting on the inside cover: “Want whatever you want more fiercely.”

Inside the book, the full Cunningham quote reads: “If I’d been a different sort of person, a braver sort, I’d taken him by the shoulders and said, ‘Want whatever you want more fiercely. Be more difficult and demanding. Or you’ll never make a life that uses you.’”

Real advice, once again masked by the dangerously codified label of fiction. Twain and Cunningham wrote about it, but Daniel Pearl actually lived it. His life used him, yes—perhaps a little too harshly. But more aptly, he used life.