Head for the Hills

The uphill climb of backcountry skiing in Southern California

-

CategoryUncategorized

-

Written bySteven Nereo

You may be surprised to learn that sunny Southern California—better known for surf than snow—actually has an expansive history of skiing dating back to the turn of the century, when a few adventurous souls traipsed through the Big Bear backcountry on homemade skis. Since those early days, the interest has ebbed and flowed, but the area’s multitude of winter options remains.

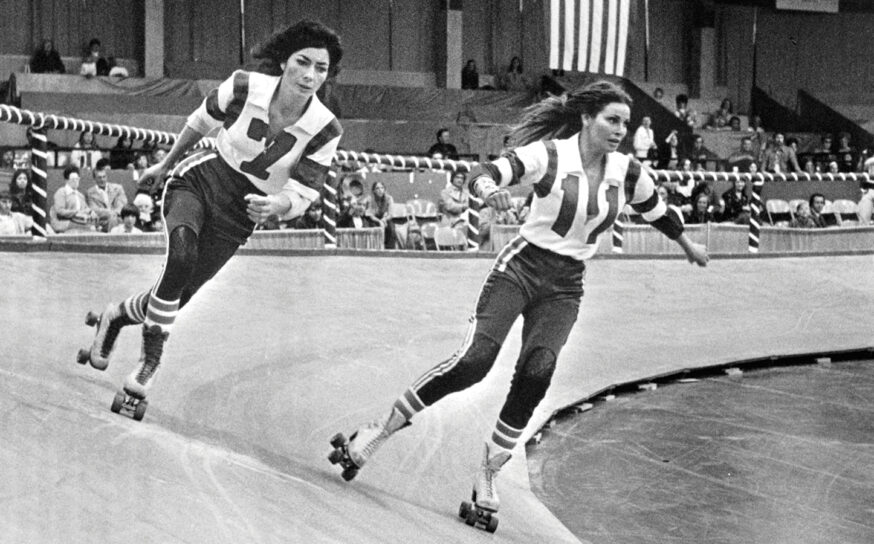

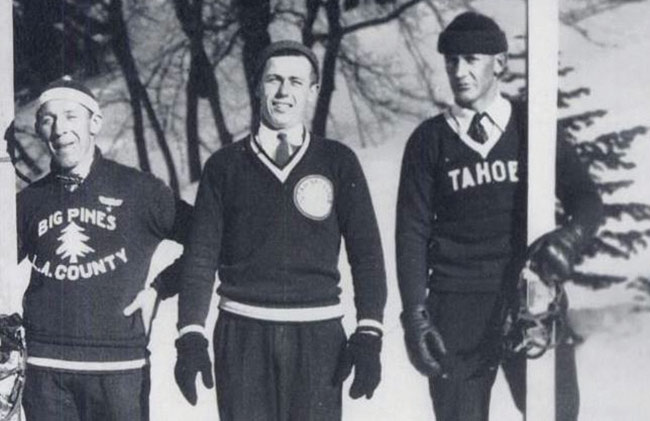

During the 1920s, the popularity of ski jumping was the driving factor for the Southland’s interest in skiing the local mountains. In 1929, Big Pines—today’s Mountain High—built the area’s first world-class jump that would quickly attract crowds in the thousands for their big events.

Yearning to bring the thrill of jumping even closer to local spectators, in 1935 a few promoters converted 25 tons of ice into a ski jump in the hills behind the Hollywood Bowl for a one-day event pitting the best local ski jumpers against one another.

By the later 1930s, ski fever had fully gripped Southern California, creating an exciting pull to the area’s mountains. Throughout the decade, the Southland saw its first ski store in Downtown Los Angeles and a weekly ski column in the Los Angeles Times, both of which lasted into the ‘50s.

There were also notable attempts to bring snowless skiing to local enthusiasts, one being a pine needle-covered slope by Universal Studios that operated in the summer of 1939. Serviced by a rope tow, visitors to the aptly named Pine Needle Ski Slope could pay for the slow thrill of gliding down the soft hill without the need for heavy coats or long commutes.

It was also in this vibrant decade that locals expanded their exploration of the area’s mountains to climb and ski. One such popular destination was Mount San Antonio, more commonly known as Mount Baldy for its exposed south-facing bowl that can easily be seen from the South Bay on a clear day.

In 1936 the newly formed Sierra Club Ski Mountaineers built the first ski hut at the base of the bowl, hauling construction supplies up a grueling three-mile hike to the site of the cabin. Unfortunately, the original cabin burned down that same year but was quickly rebuilt and is still available for visits today.

Big Pines ski jump

The first chairlift in Southern California —and the second in the entire state—was erected in the hills north of Los Angles at Mount Waterman in 1942. Even so, lift skiing was still limited, so those early days were mostly spent backcountry skiing—the act of climbing or “skinning” up the mountain before skiing down. (“Skins” are the covers on the base of the ski that allow for grip on the way up; they are removed for the descent.) The advantage of backcountry skiing is the ability to explore any mountain regardless of whether ski areas exist.

San Gorgonio Mountain, on the eastern edge of the San Bernadinos, was another popular destination for backcountry skiers. In 1940 a race was held that developed into a yearly tradition. With a six-mile walk-in and climb, the race was as much about getting to the starting line as the descent itself.

Sporty attire for California ski clubs

The event continued yearly into the ‘50s as one of the last “hike-up” races in the world. Mount Baldy was also host to another popular race in the ‘30s and ‘40s, with skiers climbing to the top of the bowl and racing to the ski hut.

As the ‘50s came around, the development of ski areas matched pace with the country’s post-war interest in recreation. Mount Baldy installed its first lifts in 1952, and other resorts followed. With closer areas and a continuing improvement of roads, cars and snow removal, skiing locally for Southern Californians was easier than ever, and they took full advantage of it in increasing numbers.

With this popularity came the desire for developers to build more lifts, and Mount San Gorgonio lay directly in their sites. As the highest of the Southern Californian peaks—standing at a height of 11,503 feet—its timber-free slopes and heavy annual snowfall were often targeted by thirsty entrepreneurs.

By 1960 the battle between conservationists and developers was in full effect, with each presenting their case to the public. In the end, the efforts of the Sierra Club and the Defenders of the San Gorgonio Wilderness, coupled with the Wilderness Act of 1964, saved the mountain’s designation as the wilderness area it remains today.

These days, the options are only limited by the year’s snowfall and your personal sense of adventure. In the past 10 years, the popularity of backcountry skiing and snowboarding has flourished with huge advances in equipment and knowledge.

Locally, the backcountry possibilities are abundant and on a good year will hold snow after the resorts have closed. The Mount Baldy ski hut still welcomes weekend visitors at an affordable rate through the Sierra Club, giving skiers direct access to the Baldy Bowl, while neighboring Mount Baden-Powell is another option for an easy day trip.

Further west stand two majestic peaks forming the gateway to Palm Springs. On the north side of Interstate 10 is San Gorgonio, while just south of that is Mount San Jacinto State Park, with snowfields that are backcountry-accessible off the tram from Palm Springs. Even if you don’t plan to ski, the tram on a recently snowed day is a spectacular sight.

For those who prefer resorts, there is the snowboard-park excitement of Mountain High, the rustic draw of Mount Baldy Ski Lifts or the higher altitude options that surround Big Bear Lake. Even Mount Waterman still opens on weekends, though without a snow-making system, it is dependent on a natural snowfall.

Mount Waterman chair lift

Of course, safety and experience are a necessity in the mountains, and trips into the backcountry are not to be taken lightly. But with the right gear, guides and enthusiasm, you are only a short trip away from being part of the continuing and exciting history of Southern California skiing.