Creature Feature

How a flotilla of bloodcurdling creations—beginning in 1923—gave birth to a monster of a movie studio in the Valley.

-

CategoryUncategorized

-

Written byPauline Adamek

Vampires, zombies, aliens.

Horror movies and creature features never seem to go out of style, enjoying a perennial popularity way beyond the Halloween season. One major Hollywood movie studio—the oldest one in town—still profits from the B movies that initially put them on the map.

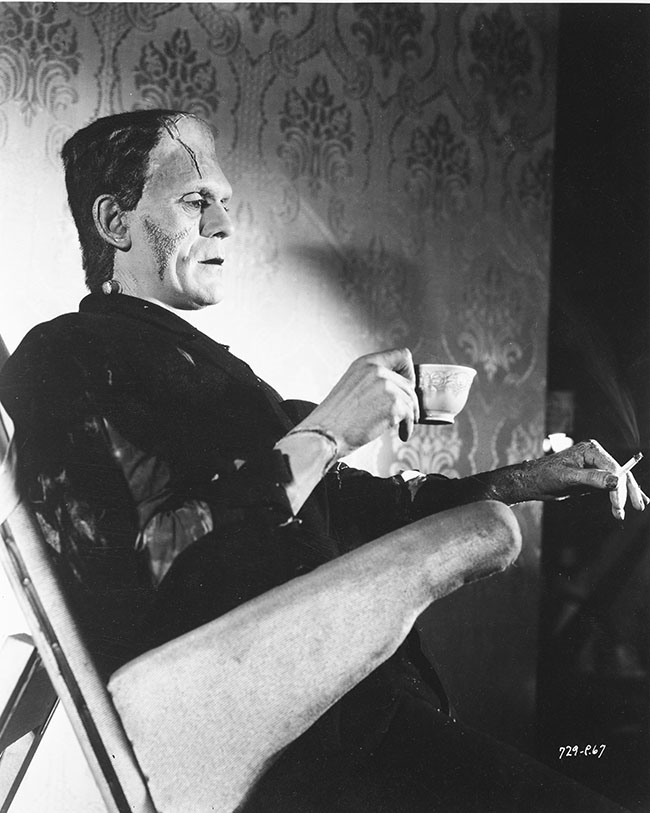

Indeed the famous large creatures, such as Frankenstein’s monster and the stealthy, bloodsucking killer vampire Dracula, formed the grisly backbone of Universal’s growth through the decades. While rival studios, such as Warner Bros., delivered highly popular gangster movies, Universal stuck to producing monsters, giant robots, aliens and otherworldly creatures.

“People have to understand that Universal was not one of the leading studios. MGM was called the ‘Tiffany’ of movie studios—everything was ‘class.’ Paramount was considered the most sophisticated studio. But Universal was a ‘bread-and-butter’ studio,” shares film critic and historian Leonard Maltin. “They didn’t own a chain of movie theaters as the other ‘big boys’ did, so they were a little scrappier.”

It was 1915 when entrepreneur Carl Laemmle opened Universal City Studios—the world’s largest motion picture production facility. He converted 230 acres of farmland just north of Hollywood on the Cahuenga Pass into a working backlot. Universal’s first few movies were generally less flashy than those released by their rival studios but proved to be crowd-pleasing fare: mostly inexpensive melodramas, Westerns and serials.

SCREEN SCREAMS

SCREEN SCREAMS

It was actually Carl’s son, Carl Laemmle, Jr. (known as “Junior”), who discovered actor Lon Chaney on the stage and decided to put him in pictures. The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1923) was a comparatively expensive picture. That, plus the unknown lead, made it a risky venture. However, Victor Hugo’s classic novel was the draw, and the studio gambled on it.

“It was a genius performance by Lon Chaney,” claims Leonard, and the movie was a hit. Soon after, Lon appeared in The Phantom of the Opera (1925), also based on a classic work of French literature, by Gaston Leroux. The two films proved to be the biggest movies that Universal produced during the silent era. As Leonard points out, Universal became, for the most part, a financially successful operation.

But the movie industry was going through a dramatic upheaval. Recalls Leonard, “When ‘talkies’ came in, ‘Uncle Carl,’ as he was called, turned the reins over to his enterprising son.” Junior took a chance on something no one had made before—horror movies.

Two big changes affected the movie industry around the early ‘30s. One was that Universal had been losing money on their lavish Broadway musicals, such as King of Jazz (1930). Observes Marc Wanamaker, a film and LA historian and owner of Bison Archives, “These musicals were so big and costly, they were starting to break the company financially.”

Additionally, sound was coming in, and all the studios had to spend vast sums building sound stages and investing in new equipment—all this at the same time as the Wall Street crash. “They couldn’t afford the facilities plus the making of the films. They were in a terrible condition,” says Marc.

CREEPY CHARACTERS

In 1931 Universal decided to do some low-budget, “shock value” movies to make money, and Dracula marked the first horror picture of the sound era. Remembering the success of 1925’s The Phantom of the Opera, Universal returned to producing creepy dramas with sinister and fantastic central characters.

“People were scared and fascinated, but everyone had to see these monster pictures,” says Marc. Paramount did Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde both as a silent, with John Barrymore, and a talkie, but with Dracula, The Wolf Man, The Mummy and Frankenstein, Universal forged a horror brand, putting their own stamp on their spooky fare.

Elaborates Marc, “Lon Chaney, thanks to his stage training, developed many character personae, including playing heavies in Westerns.” Famous for transforming himself into tortured, grotesque characters by using disfiguring makeup and contorted postures, Lon became known as “The Man of A Thousand Faces.” The studio chiefs realized they could count on him, and he gradually worked his way up in popularity at Universal.

“They gave him the big chance to become a big star,” continues Marc. “He had to put on so much special makeup for those roles that were over-the-top incredible and shocking, and the studio banked on him being successful doing this. And they were correct.”

The Lon Chaney silent movies paved the way for horror pictures, even though they were Gothic melodramas more than anything. “When Junior took a risk with Frankenstein and Dracula, it was a daring move,” says Leonard Maltin.

Once again, in launching these two movies of this untested genre, Junior lacked the draw of marquee power to back him up—the leads were unknown. Bela Lugosi was far from being a movie star, even though he had created the role on Broadway. And for his iconic performance as Frankenstein’s monster, Boris Karloff didn’t even get billing!

Today the film’s credits still read “The Monster?” This was done to preserve the mystery of the creature’s true identity—that of a mere actor. Recalls Leonard, “Those were the days before Hollywood gave all their tricks away, quite unlike today.”

While today it’s standard to produce sequels to anything that performs at the box office, that was not the case back then. “They would do copycat films, though. They weren’t above that,” Leonard laughs. “They’d be clones but not actual sequels.”

That Universal kept going back to the well was indicative of the enormous box office pull and power of their spooky films and their creepy characters. Comments Leonard, “People really were scared by those early pictures. They’d never seen anything quite like it.”

Next came The Mummy (1932) starring a terrifying Boris Karloff as the bandaged animated corpse and also Werewolf of London (1935)—the first Hollywood mainstream werewolf flick. It paved the way for 1941’s The Wolf Man, which starred the son of “The Man of a Thousand Faces”—Lon Chaney, Jr.—who carried on his father’s legacy through talking pictures.

The “sons,” and “brides” pictures also hit the screen, like The Bride of Frankenstein (1935) and Son of Frankenstein (1939).

Based on H.G. Wells’ science fiction novel about a hapless scientist, Universal released The Invisible Man in 1933. Claude Rains provided the disembodied though mellifluous voice when he wasn’t obscured by bandages.

Says Leonard, “I suppose you would call him sci-fi, but it landed in the midst of these films because Universal was the home of fantastic story-telling. The Invisible Man Returns, The Invisible Woman, Invisible Ghost—Universal really knew how to milk it.”

SCARY MOVIE

A scene from The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1923) with Lon Chaney and Patsy Ruth Miller.

MONSTER RE-MIX

The original Frankenstein and Dracula movies were continually resurrected and rescreened at picture houses all over the country many years after their first release. As Maltin points out, “These films had enormous staying power.”

Universals’ monsters also experienced a rebirth when television came along. The widespread success of the package of old horror movies syndicated to American television in 1957 spawned the hugely popular magazine Famous Monsters of Filmland. Originally conceived as a one-off publication by James Warren and Forrest J. Ackerman, the magazine enjoyed a decade of hard-core prosperity.

This symbiotic association led to a whole new wave of interest in horror, fantasy and science fiction. The Famous Monsters magazines were avidly devoured by Stephen King, Steven Spielberg and George Lucas—writers and filmmakers who went on to thrill audiences and break new ground with their blockbuster works.

Audiences of the 1950s post-war, post-atomic bomb era were fascinated by the extra-terrestrial thrill of the space race. Universal released It Came From Outer Space (1953), Creature from the Black Lagoon (1954), Tarantula (1955)—all B movie creature features.

THE LEGACY LIVES ON

More than a half-century after their golden years of monster movies, Universal has continued to capitalize on its homegrown creatures. Three of Universal Studios’ more recent releases broke box office records, each becoming the highest-grossing film made at the time. All were “creature features,” namely Jaws (1975), E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial (1982) and Jurassic Park (1993).

As Leonard Maltin sums it up, “For Universal, monsters became their hallmark. Here we are, still talking about this 80 or so years after their creation. That’s pretty amazing!”